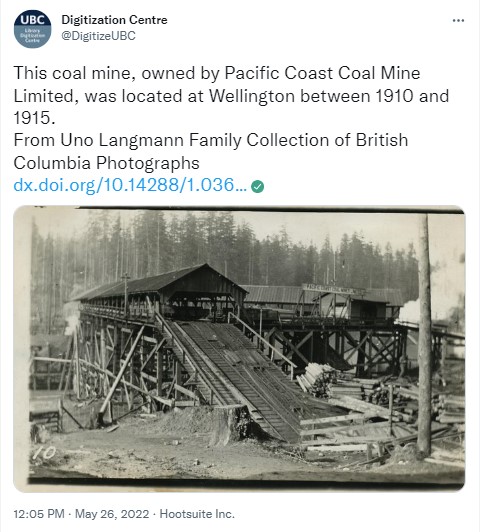

I work as the Digital Collections Assistant at the Vancouver Island University Library, and as a summer project, I was doing some reparative description work on one of the library’s electronic collections – the Coal Tyee History Project. This collection is made up of audio recordings and transcripts of interviews with Vancouver Island coal miners and their family members and is hosted online in VIU’s open access institutional repository, VIUSpace. The interviews were conducted between 1979 and 1984 by the Coal Tyee Society, and most interviewees were from the coal-mining communities of Nanaimo and Cumberland. Transcripts in the collection were primarily created by the society, with just a few missing ones completed afterwards by the VIU Library Technical Services Department.

While working through the collection I was able to correct several small spelling or transcription errors: Armanesco became Armanasco; Bodovinick became Badovinac; and Matthew Clue became Martin Clue. While these may seem like minor changes, I think they are ones that could potentially go a long way in increasing the likelihood of connecting researchers, or even family members, with these interviewees.

Interesting details about the experiences of women during the coal-mining era are embedded in the interviews of the Coal Tyee History Project. Male interviewees talk about the women in the community: teachers, nurses, and the women who worked in the Hamilton Powder Company’s explosives plant that supported the mine industry. Multiple Coal Tyee History Project interviewees recalled the nurse who entered the coal mine without permission. The collection also includes an extensive interview with Dorothy “Dolly” Gregory, who worked with her husband at their small family-run mine. Women’s stories are not the dominant narrative in the Coal Tyee History Project, but they are valuable for adding to our understanding of coal mining on Vancouver Island.

“Mrs. Frank Wall”

Although the Coal Tyee Society interviewed several women, their full names are sometimes not documented. As an example, a 1979 interview with “Mrs. Frank Wall” had no accompanying details about what Mrs. Wall’s first name was.

To be fair, the transcript shows that Mrs. Wall agreed to being identified as “Mrs. Frank Wall” during the interview. Her initials in the transcript appear as “MW” for “Mrs. Wall.”

SR: I’d like your full name. Mrs. Frank Wall is it? W A L L?

MW: Yes.[1]

This naming practice, where a woman was identified only by her husband’s name, dates back to the Middle Ages, when under the doctrine of coverture, a married woman’s identity, especially her legal identity, was tightly tied to her husband’s. Although not actually practised for centuries, the remnants of the doctrine of coverture can still be seen in the symbolic practice of people adopting their spouse’s surname after marriage.

While not a choice that every newlywed opts for, even today, some folks decide to start using their spouse’s surname after marriage. But can you imagine also letting go of your first name too? Mrs. Wall, it’s time for you to be properly identified!

There were a couple of clues in the transcript, notably that Mrs. Wall’s maiden name was Roberts.

MW: Oh, why not start with my dad when he came across?

SR: Wonderful. And when was that?

MW: He landed in Frisco on his 21st birthday.

SR: And what was his name, Wall is your married name?

MW: Yes. It’s Roberts.

SR: Roberts.[2]

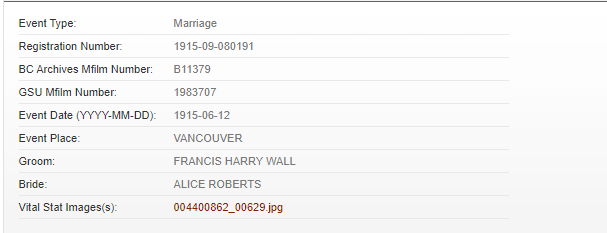

It took one attempt using the BC Archives Genealogy search tool to find Francis Wall and Alice Roberts’s marriage record from 1915.

Screenshot from a BC Archives Genealogy search

This seemed like a slam dunk, but I wanted to have at least one other source that confirmed Alice as Mrs. Wall’s first name. In the interview, Mrs. Wall also refers to her family’s story as being in “the Nanoose history book.”

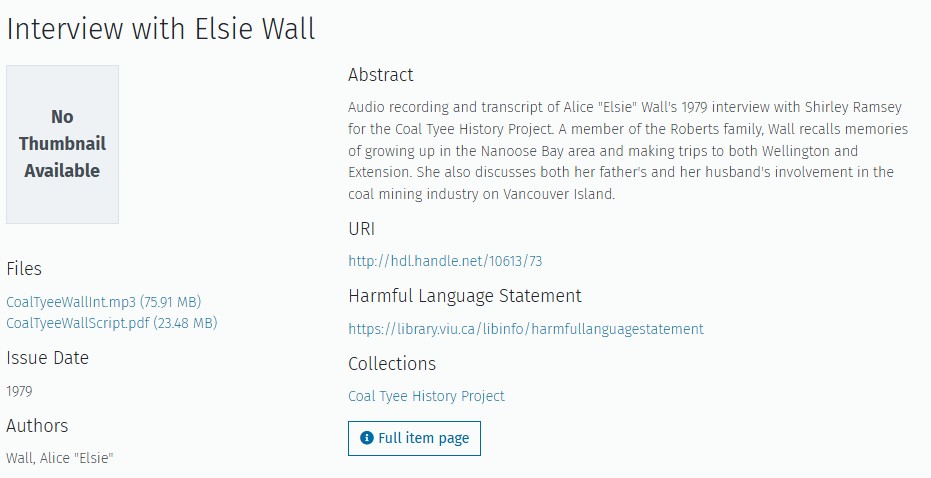

I’m both a book collector and interested in Vancouver Island’s history, so I knew what book she was talking about, and I happened to have a copy on my shelf at home. Both the Roberts and Wall families have many entries in the index of the 1980 second edition of A History of Nanoose Bay, but when I looked up one of the Alice Wall references, I found another little detail: “Frank Wall came to Nanoose with his father in 1913. He married Alice (Elsie) Roberts and they lived on the old William Wall property at the mouth of Craig Creek. In 1976, Elsie Wall deeded the entire property, 80 acres, to the Government of B.C. as a memorial to her husband.”[3]

It seems like Alice went by the name Elsie (perhaps because her mother’s name was also Alice). So, it was definitely worthwhile to dig a little deeper.

After I did this sleuthing, I went back to the audio file in VIU’s collection and listened very closely to the recording. And once I knew what I should be listening for, I heard it. It’s not captured in the transcript, but during the interview, Mrs. Wall shares her mailing address and in doing so she gives her name as Alice Wall. A reminder to those who work with oral histories – it’s important to go back to the original source.

Elsie Roberts Wall circa 1940

image courtesy of the Parksville Museum Archives (parksvillemuseum.com).

Nanooa Historical Society Collection, PMA 03. Scrapbook 3.20 Roberts

I remembered that copies of the Coal Tyee History Project recordings and transcripts were also deposited at the BC Archives. I checked the record for the Wall interview, and they’ve assigned the first name “Margaret” to Mrs. Wall. I’m not sure how they decided on that, as there’s no mention of Margaret in the transcript nor does that name appear in the index of the Nanoose Bay history book.

I’d like to welcome Alice “Elsie” Wall to VIUSpace! I see you now and hopefully others will too.

“Before and after” screenshots of the Wall interview record in VIUSpace:

“Mrs. J. Hunt”

Similar to Elsie Wall, another interviewee was identified only as “Mrs. J. Hunt”. Mrs. Hunt’s first name was a bit harder to track down. In the interview, she mentions a daughter, Jean, who was a ballerina. A Google search for “Jean Hunt” AND ballerina led down a fascinating rabbit hole about the successful Canadian ballet dancer who used the stage name Kira Bounina while touring internationally.

But once again, a little sleuthing using the BC Archives Genealogy search tool managed to uncover Mrs. Hunt’s identity. A search for females with the surname Hunt who died in Nanaimo after 1979 (the year the interview took place) returned only six results. Hazel Melvina Hunt’s death certificate was signed by her daughter Jean Haet.[4] Haet was Jean Hunt’s married name. We have a match!

Hazel’s husband Jack had been a well-known mine manager, so it makes sense that the Coal Tyee Society sought her out for an interview. Even though she is repeatedly asked questions about her husband throughout the interview, she also talks about her own family connections to coal mining, her impression of Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company superintendent Samuel Robins, and her memories of Nanaimo. Hunt recalls the Oscar explosion, she tells stories about her brother, and she talks about miners’ picnics on Saysutshun (Newcastle Island). Just because she was the wife of a mine manager didn’t mean that she didn’t have her own thoughts, feelings, and experiences about coal mining on Vancouver Island.

Women of the coal-mining era had stories to tell. The Coal Tyee History Project includes women speaking about their roles as homemakers, and about their lives as the wives, mothers, siblings, and daughters of coal miners. Their memories have depth and meaning and can add to our knowledge about the history of coal-mining communities.

“Mrs. U” & “Mrs. S”

There were also multiple unnamed women included in Coal Tyee History Project interviews. Sitting in on interview sessions with male relatives, friends, or neighbours, they are not formally introduced on the recordings. Sometimes their presence was noted on the transcripts, but often information about their identities was vague or incomplete.

Ida Unsworth is noted only as “Mrs. U” in the transcript of the interview she participated in with her husband Jack Unsworth; Delfina Senini is “Mrs. S” which was tough to decipher as she is interviewed in conjunction with Dominic Armanasco, who was a relative that had boarded at her home.

Ida Unsworth grew up in the coal-mining community of Extension and had girlhood memories of the coal dump in the community:

Mrs. U: We filled our buckets when we came home from school. I was only a small girl, but I remember that.[5]

As an adult woman, now married to a coal miner, her thoughts on mining shifted to safety:

MB (To Mrs. U): And how did you used to feel about it, you were so used to mining, I guess, that you didn’t worry about it when he went out to work.

Mrs. U: I worried an awful lot about it. Because he was by himself.[6]

Jack and Ida Unsworth

image courtesy of the Unsworth family

The short comments by Unsworth that are interspersed in her husband’s almost one-hour-long interview may not seem like much on the surface, but they contribute to our understanding about what it was like for girls and women to live in coal-mining communities on Vancouver Island. They were there. They lived with coal miners and looked after their homes and children. They worried about the men in their lives and were there at the mine site after accidents happened. They also experienced the challenging economic times related to the industry and had thoughts independent of their menfolk.

Mrs. S: My daughter says, I wish I am like you, so thrifty! I tell her you got to learn like through the depression, like we did.

MB: So, if you had to do it over again, would you do it over again?

Mrs. S: No, I’m sure not.

DA: It’s hard to tell, now.

Mrs. S: No, I could not do it now. I could not carry the water and wash clothes.

MB: Some people say, Oh yes, they would do it all over again.

Mrs. S: Oh no, not me! But we have to! Have to, no use, you know.[7]

Amplifying Women’s Voices

Birth, death, and marriage records, newspapers, directories, genealogical tools, obituaries, and regional history books can all be used to track down these hidden women. It can take a little digging, but often, it’s possible to uncover their full names, and in the case of the Coal Tyee History Project, to update the historical record by including metadata that fully identifies them.

By not including the full names of these women anywhere in the descriptive metadata for the Coal Tyee History Project interviews, their stories aren’t very accessible, and their voices aren’t always being heard. I view this as something that contributes to a problem that I’ve seen referred to as “archival silence.” When individuals are not correctly named, it has an impact, and it’s not a good one. Libraries and archives are not neutral, and like other historically silenced peoples and communities, women’s presence in the historical record has not been as prominent as men’s and I’m happy to help elevate women’s nuanced experiences any way I can. Descriptions and metadata can be improved to help confront the bias in library collections and to help reshape and reform how context for digital objects is provided. Straight-white-male narratives aren’t the only story. So, for those of us who have the opportunity to do this work, let’s go ahead and challenge ourselves to provide new and better ways to discover and access materials related to underrepresented voices.

Notes

[1] Alice “Elsie” Wall, interview by Shirley Ramsey, Interview with Elsie Wall, VIUSpace, 1979, http://hdl.handle.net/10613/73.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Barbara Prael Sivertz, compiler, A History of Nanoose Bay, 2nd ed. (Nanoose: Nanoose Volunteer Fire Department Ladies’ Auxiliary, 1980), 56.

[4] Registration of Death for Hazel Melvina Hunt, 8 February 1983, Registration No. 83-09-002785. Province of British Columbia (Canada) Department of Health Division of Vital Statistics.

[5] Ida Unsworth, interview by Myrtle Bergren, Interview with Jack Unsworth, VIUSpace, 1979, http://hdl.handle.net/10613/176.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Delfina Senini, interview by Myrtle Bergren, Interview with Dominic Armanasco, VIUSpace, 1979, http://hdl.handle.net/10613/124.