I’m happy to be writing a series of blog posts about my great-grandparents, Ole Olsen and Konstanse Fyhn. This third installment is the story of the Olsens’ time in the Bella Coola Valley after their marriage in December of 1914 until they left the valley in early 1935.

While many of the original Norwegian settlers in the Bella Coola Valley had dreams of making a living off the land and selling produce to support themselves, this proved to be challenging. Diana French, an author based in the Cariboo Chilcotin region, reflects on how the original colonists must have wondered at their choice: “The valley was dreary. The mountains loomed over the newcomers, critical of every move. There were no open meadows in the valley. Every inch of land was buried under thick tangles of brambles and bush, windfalls and enormous trees.”1

While the land they had heard promising tales of did prove to have rich alluvial soil, great for growing potatoes and fruit trees, massive trees covered everything in sight. The river, with its frequently shifting flood plain, was also a challenge to farmers living on its banks. But probably the biggest impediment to the colonists making a living from the fruits of their labour was the lack of access to the Bella Coola Valley, and “by 1915 everyone realized that the valley’s remote location made full-scale farming a chancy business.”2

To earn a living, many of the men of the Norwegian community, my great-grandfather Ole included, worked as commercial fishermen, spending long periods of time away from home. Ole fished salmon in Rivers Inlet from spring to autumn, and sometimes went out again in November, when he headed to the west coast of Vancouver Island to fish the runs there. With a can of salmon considered the ideal army ration, B.C. salmon was in demand during World War I.3 Fishermen like Ole would have likely found plenty of demand for their catch. But other times were tougher. “In the very early twenties the fishing was not rewarding,”4 local historian Cliff Kopas records in his history of Bella Coola. Families likely had to subsist on what their garden could provide them. “In a poor fishing year, the women probably made more of what they realized in the garden than the men did.”5

The Olsens circa 1923 – Konstanse, Arnold, Einar, Ole, and Johnny

The Olsens circa 1923 – Konstanse, Arnold, Einar, Ole, and Johnny

With the men away for long periods of time fishing, the women were frequently left to take on most of the responsibilities at home, including raising the children and tending the farm. With young ones to care for, animals to mind, household tasks to be done, bread to bake, and gardens to plant, weed, and harvest, women like my great-grandmother Konstanse would have had more than enough chores to keep themselves busy. Perhaps this helped to distract Konstanse from her loneliness, for “the lot of a fisherman’s wife was a solitary one in rural British Columbia.”6

Ole was joined fishing by his sons as they aged, with his oldest son Johnny eventually running a boat of his own. In what seems to be a very popular generic “Norwegian fisherman in Bella Coola” image, a young Johnny Olsen is captured in a photo taken by Cliff Kopas, who in addition to being a local historian was also an avid photographer. The image turned up in multiple books that I read during my research. My grandmother always claimed that her brother was in a “famous” photo, but the young fisherman I encountered again and again was always unidentified. Finally, in a book edited by Kopas’ son Leslie, I found a proper caption for the photo. It was Johnny after all, my grandmother’s eldest brother. What a nice surprise!

Johnny also makes an appearance as an eager but green cowboy in Isabel Edwards’ book Ruffles on My Longjohns, which chronicles the Edwards family’s experiences homesteading in the Bella Coola Valley. “The saddle was for a young Hagensborg chap named Johnnie Olson [sic] whom Earle had met out on the fishing grounds. Johnnie longed to be a cowboy. His only dream was to ‘ride the hurricane deck of a cayuse,’ but he had no saddle, nor a horse to put one on.”7 After his pack horses desert him and he has to spend a night out alone in the cold with no axe or matches, Edwards says Johnny changed his mind about his dream and “with an air of finality the words burst from him, ‘But to hell with horses!'”8 So it was back to fishing for Johnny Olsen, and in a cruel twist of fate, Bella Coola’s iconic fisherman died doing what he knew best. Having never learned to swim, Johnny presumably drowned in 1969 while fishing off the coast of Prince Rupert. His body was never recovered.

The Olsens circa 1930 – Back row: Ole, Konstanse, Eva, Johnny, and Arnold;

The Olsens circa 1930 – Back row: Ole, Konstanse, Eva, Johnny, and Arnold;

Front row: Olive, Henry, Herb, and Einar

In October of 1934, after a heavy snowfall followed by an unusual warm spell and multiple days of rain, the Bella Coola River rose swiftly and flooded the Olsens’ property near Hagensborg. Ole and Johnny were away fishing at the time, so Konstanse was the only parent at home with the eight younger children as the river rose closer and closer to the house. Baby Robert was just a few weeks old at the time. The family sheltered in the house, feeling especially terrified after “away out in the night there came the most awful shock. As though the house itself were falling to pieces. … Arnold instantly interpreted: ‘The Branch bridge.'”9 The Olsens’ farm was located on an island which was connected to surrounding land by two bridges. The children were upset; they were out of drinking water, and the river continued to rise. A second roar indicated the main bridge also being washed away.

Great tree trunks from a dislodged log jam struck “the house so hard the whole place shook and faltered as though the boards were being warped crazily and all the nails pulled out at once. It struck them dumb.”10 With trees racing through the flood waters like battering rams, the river was no place for the family’s small rowboat, and they were trapped on their island. The Olsens prayed.

And their prayers were answered. Together with a crew of Nuxalk paddlers, the local doctor from the Mission Hospital, Dr. Herman McLean, and the provincial police constable, whom I believe was Jack Condon, rescued the Olsens in two great spoon canoes. My grandmother’s brother Einar remembered one of the Nuxalk rescuers as being Clayton Mack, later known as “The Bella Coola Man.” While I didn’t find any reference to Mack rescuing a flooded-out white family in 1934 in either of his biographies, it’s the kind of tale that would fit right in with Mack’s other adventures. Mack would have been approximately 24 years old at the time of the flood. A canoe rescue might have been not only enticing for its sense of adventure, but also quite doable given his familiarity with the area and in handling canoes. He certainly rescued his fair share of others from all sorts of wilderness scrapes during his many years as a grizzly bear guide in the Chilcotin. So, while I may never confirm that Clayton Mack was among the Olsens’ rescuers, it sure makes a good Bella Coola tale.

“I remember being in that flood, raging water everywhere, tree trunks, chickens, and planks swirling past us,” my grandmother Eva recalled.11 The family was loaded into the two great canoes, and the children were told to “Sit still!” with “enough authority in it to silence nearly forever all the rambunctious, disorderly kids in the whole world.”12 Einar remembered being scared and excited, and when interviewed about the flood he confided: “I almost wet my pants!”13

But the Olsens weren’t in the clear yet. When the canoes were beached on a sandbar, the family had to unload. The shifting sands caused Einar to lose his footing and he disappeared into the river with his baby sister Eleanor in his arms. A Nuxalk paddler grabbed Einar by the hair and pulled and the two Olsens were rescued a second time, “the infant still clasped in [Einar’s] unyielding grasp.”14 What a terrifying ordeal. It’s no wonder that, as my father’s cousin aptly wrote in a newspaper article about the Olsen family, “this harrowing story continues to be one that is retold in our family and handed down through the generations.”15

The 1934 flood was the largest in the valley in 60 years.16 With 11 acres of their land swept away, and a house that would never be the same, the Olsens’ farm was a grim picture. My grandmother’s brother Einar reflected in a 1998 interview: “We didn’t recognize the place. … There had been two benches of land and now it was all changed. There was six feet of river silt where there had been green grass and water had ruined everything in the house. All the years of hard work were destroyed.”17

It was time for the Olsens to leave the Bella Coola Valley.

Notes

- Hank Olsen, Bella Coola Lady and That’s No Maybe (Victoria, BC: Trafford Publishing, 2003), 28.

- Paula Wild, One River, Two Cultures: A History of the Bella Coola Valley (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2004), 125.

- Mark Forsythe & Greg Dickson, “The Gift of Salmon,” in From the West Coast to the Western Front: British Columbians and the Great War (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2014), 68.

- Cliff Kopas, Bella Coola (Vancouver: Mitchell Press, 1970), 266.

- Gordon Fish, Dreams of Freedom: Bella Coola, Cape Scott, Sointula (Victoria: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1982), 42.

- Olsen, Bella Coola Lady and That’s No Maybe, 33.

- Isabel Edwards, Ruffles on my Longjohns (North Vancouver: Hancock House, 1980), 241.

- Edwards, Ruffles on my Longjohns, 242.

- Olsen, Bella Coola Lady and That’s No Maybe, 128.

- Olsen, Bella Coola Lady and That’s No Maybe, 130.

- Eva Johnson, diary entry.

- Olsen, Bella Coola Lady and That’s No Maybe, 132.

- Wild, One River, Two Cultures, 164.

- Olsen, Bella Coola Lady and That’s No Maybe, 132.

- Marcy (Olsen) Green, “An Immigrant’s Journey: The Olsen Family,” The Vancouver Sun, April 29, 2008, B3.<

- D. Septer, Flooding and Landslide Events in Northern British Columbia, 1820-2006, ([Victoria, BC:] Ministry of Environment, [2007]), 28, http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wsd/public_safety/flood/pdfs_word/floods_landslides_north.pdf.

- Wild, One River, Two Cultures, 164.

In 2019, a Memorandum of Agreement was signed between the NHS and VIU Library allowing for a second set of NHS cassette tapes to be temporarily transferred to the Library with the intention that they would also be digitized and made available online. The NHS was again concerned about the lifespan and accessibility of an aging cassette tape collection, while VIU Library perceived value in facilitating preservation and access to local- and BC-focused content to support new lines of inquiry and study for students, researchers, and members of the community. Working within the context of its strategic plan, which includes decolonization and community engagement objectives, the Library took steps to make its services and supports known and available to the Nanaimo Historical Society.

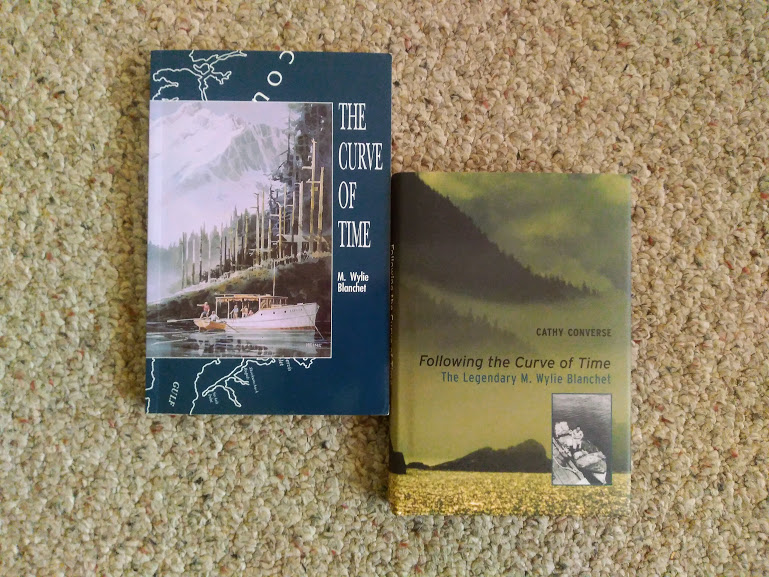

In 2019, a Memorandum of Agreement was signed between the NHS and VIU Library allowing for a second set of NHS cassette tapes to be temporarily transferred to the Library with the intention that they would also be digitized and made available online. The NHS was again concerned about the lifespan and accessibility of an aging cassette tape collection, while VIU Library perceived value in facilitating preservation and access to local- and BC-focused content to support new lines of inquiry and study for students, researchers, and members of the community. Working within the context of its strategic plan, which includes decolonization and community engagement objectives, the Library took steps to make its services and supports known and available to the Nanaimo Historical Society. Consisting of family histories, recollections about school days, book talks by local authors, and presentations about a variety of Nanaimo and Vancouver Island events, businesses, buildings, people, and organizations, the collection is truly a treasure trove of material for anyone interested in the area’s human, industrial, built, or natural history. Like everything in VIUSpace, the Nanaimo History Project is open access, meaning anyone can listen to the recordings – you don’t need to be a VIU student or staff member.

Consisting of family histories, recollections about school days, book talks by local authors, and presentations about a variety of Nanaimo and Vancouver Island events, businesses, buildings, people, and organizations, the collection is truly a treasure trove of material for anyone interested in the area’s human, industrial, built, or natural history. Like everything in VIUSpace, the Nanaimo History Project is open access, meaning anyone can listen to the recordings – you don’t need to be a VIU student or staff member.

Road from Departure Bay plant to Northfield plant,

Hamilton Powder Company, Nanaimo, BC, 1909

Photo

Road from Departure Bay plant to Northfield plant,

Hamilton Powder Company, Nanaimo, BC, 1909

Photo  CIL crates and blasting machine

photos courtesy of Janice Keaist & Maechlin Johnson

CIL crates and blasting machine

photos courtesy of Janice Keaist & Maechlin Johnson